The Federal Exchange Model

The Federal Exchange (healthcare.gov) has helped expand access to health insurance coverage and provided a streamlined alternative to building state-based systems. It does, however, carry tradeoffs for states in terms of costs, branding, data access, and policy flexibility. For some states, the features of the Federal Exchange remain a practical fit; for others, the limitations are increasingly creating pressure to reassess whether the model serves their long-term needs.

Executive Summary

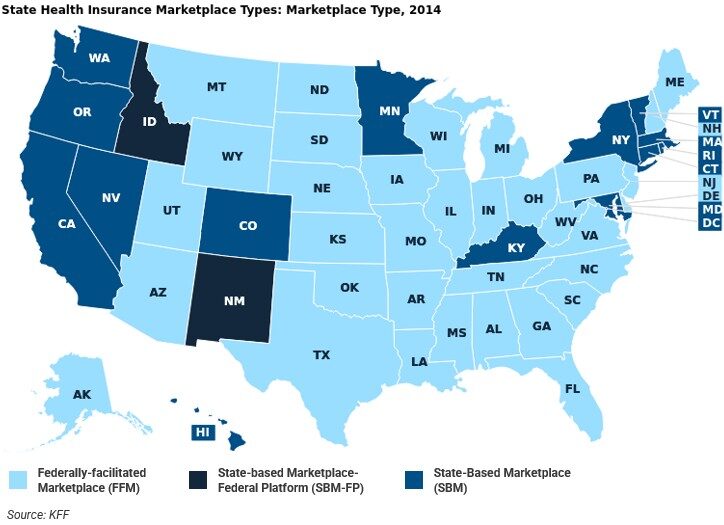

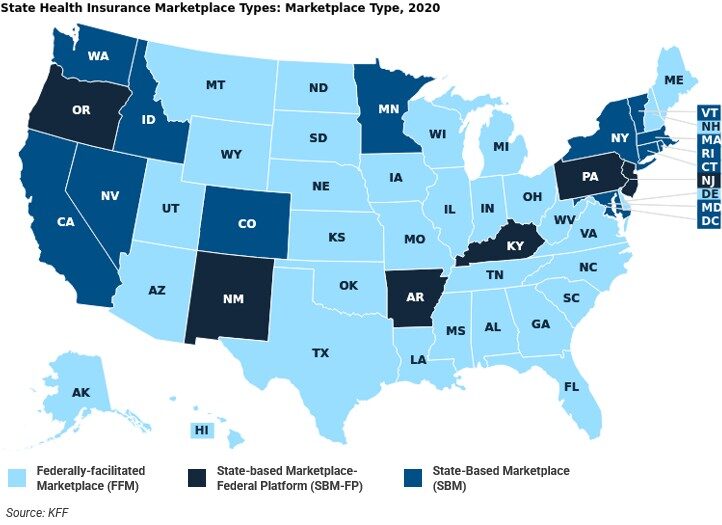

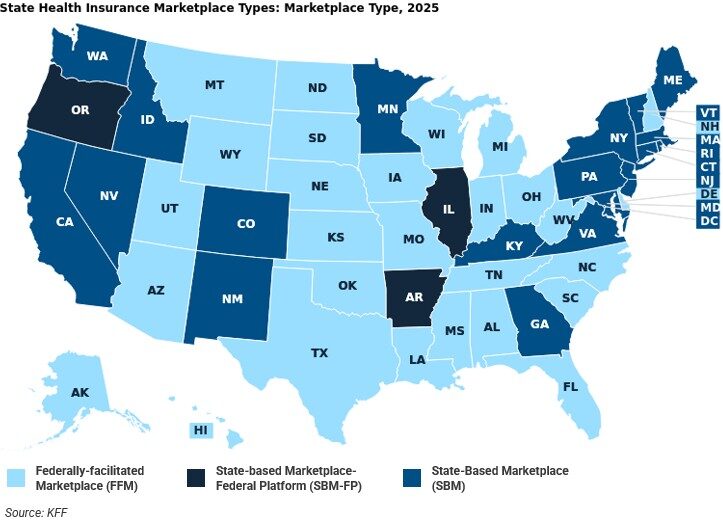

Figure 1

Introduction

The Affordable Care Act (ACA) established health insurance marketplaces with the goal of expanding access to affordable health insurance coverage, increasing transparency in plan shopping, and delivering federal subsidies to eligible individuals and families. From the outset, the law gave states flexibility: they could operate their own SBM, rely on the Federally Facilitated Marketplace FFM through HealthCare.gov, or adopt a hybrid SBM-FP. For states that chose not to build their own systems or did not meet federal readiness standards, the federal exchange functioned as a default mechanism to provide access.

Analysis

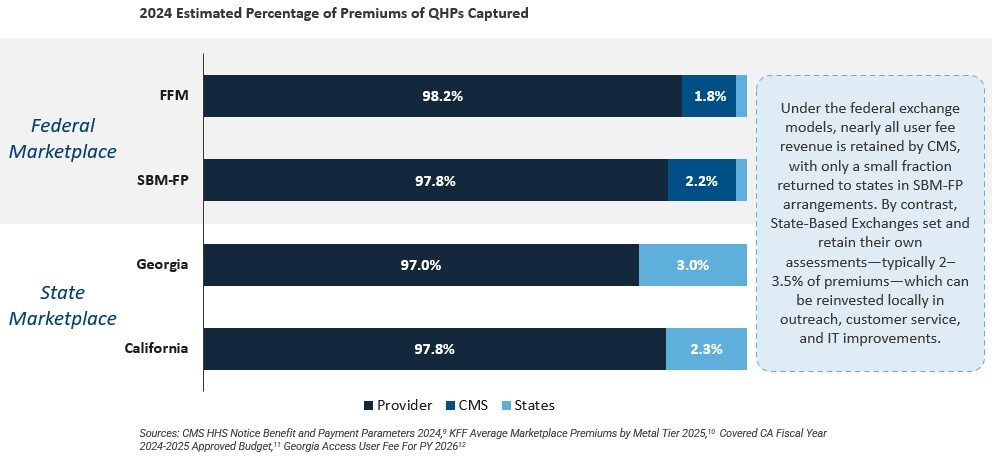

Constraints of the Federal Exchange

Figure 2

What MGT Thinks

There is no single “correct” answer to exchange models. The federal platform may be the best fit for some states, while others gain significant advantages from implementing an SBM. What matters is intentionality—states should not retain their marketplace structure from 2014 because of inertia, but should actively consider whether their current approach is meeting their residents’ needs and supporting the state’s long-term policy goals.

- How important is branding and local outreach to your enrollment strategy?

- Do you need real-time granular data access to drive policymaking, or is federal-level reporting sufficient?

- How well does your current exchange align with Medicaid, CHIP, and other state programs?

- What level of cost neutrality, fee control, and reinvestment in state initiatives would you like or do you require?

- How much flexibility do you want to adjust subsidy structures, enrollment periods, or benefit designs?

These questions can inform a decision framework to consider whether an adjustment of your current exchange model may make sense. States that place high value on branding and outreach, data access, policy flexibility, and local control of user fees, for example, may find that SBMs offer greater strategic alignment. Conversely, states that prioritize administrative simplicity and lower infrastructure requirements may conclude that the federal model is the better fit.

The experience of the 20 states and the District of Columbia that have successfully implemented SBMs since 2014 provides evidence that the model is durable and operationally effective. With new policy and legislative dynamics (and uncertainty) on the horizon, states will do well to evaluate their current approaches and prepare to adapt quickly to meet the needs of their citizens. State leaders have a responsibility to their constituents to always be asking, “Does our current model serve our residents in the best way possible?”

Call to Action

MGT’s State & Local Management Consulting Team can help your state examine and answer these questions. We have developed a comprehensive state-based marketplace assessment that provides a structured framework to evaluate your exchange model across the five key dimensions outlined above. This solution delivers a comparative cost–benefit analysis tailored to your state’s circumstances, enabling leaders to make informed, intentional, evidence-based recommendations.

Our advisory services include:

- Current State Assessment: Evaluate whether your current exchange model aligns with resident needs and policy priorities.

- Impact Analysis: Model the financial, enrollment, and policy impacts of adopting an SBM, remaining on the federal exchange, expanding targeted outreach efforts, etc.

- Implementation Planning: Provide project management and technical assistance for states pursuing transitions.

- Peer Learning: Leverage insights from the coalition of states that have successfully launched SBMs and sustained them over time.

References

1 https://www.gao.gov/assets/gao-17-258.pdf

5 https://www.gao.gov/assets/gao-17-258.pdf

6 https://www.cms.gov/files/document/ffe-enrollment-manual-2024-5cr-082024.pdf

7 https://sbm-university.thinkific.com/courses/state-based-marketplace-101

8 https://www.cms.gov/newsroom/fact-sheets/hhs-notice-benefit-and-payment-parameters-2025-final-rule

9 https://www.cms.gov/newsroom/fact-sheets/hhs-notice-benefit-and-payment-parameters-2024-final-rule

12 https://georgiaaccess.gov/insurance-companies/

13 https://unitedstatesofcare.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/03/Benefits-of-SBMs.pdf

14 https://www.shvs.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/01/SHVS_State-Examples-of-Medicaid-Community-Engagement-Strategies.pdf

15 https://www.kff.org/affordable-care-act/state-indicator/marketplace-enrollment/?activeTab=graph¤tTimeframe=0&startTimeframe=5&selectedRows=%7B%22states%22:%7B%22colorado%22:%7B%7D,%22virginia%22:%7B%7D%7D%7D&sortModel=%7B%22colId%22:%22Location%22,%22sort%22:%22asc%22%7D

16 https://data.healthcare.gov/

17 https://harvardlawreview.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/01/135-Harv.-L.-Rev.-1007.pdf