The State-Based Exchange Model

State-Based Exchanges (SBEs) provide states the opportunity to shape their own health coverage strategies, offering flexibility beyond the Federally Facilitated Marketplace (FFM) and State-Based Marketplace on the Federal Platform (SBM-FP) models. While federal models provide consistent national infrastructure, SBEs allow states to tailor policy, reinvest marketplace funds locally, strengthen their marketplace identity, and coordinate with Medicaid programs to support coverage continuity. As states explore long-term strategies to improve affordability and access, many are evaluating SBEs as a path to greater policy control and local impact.

Executive Summary

Since the launch of the Affordable Care Act, health insurance marketplace models have steadily shifted toward SBEs. In 2015, 14 states and D.C. operated SBEs; by 2025, that number has increased to 20.1,2 While the FFM offers a reliable national platform, states continue to assess whether greater marketplace control at the state level can help them achieve long-term goals and priorities around affordability, access, and control.3 SBEs allow states to retain marketplace user fees for reinvestment, customize plan and enrollment policies, strengthen local marketplace branding, and coordinate more seamlessly with Medicaid to reduce churn following eligibility changes.4 As marketplace strategy evolves nationwide, SBEs are increasingly viewed not simply as an alternative to federal infrastructure, but as a platform that enables state innovation and sustainable coverage growth.4

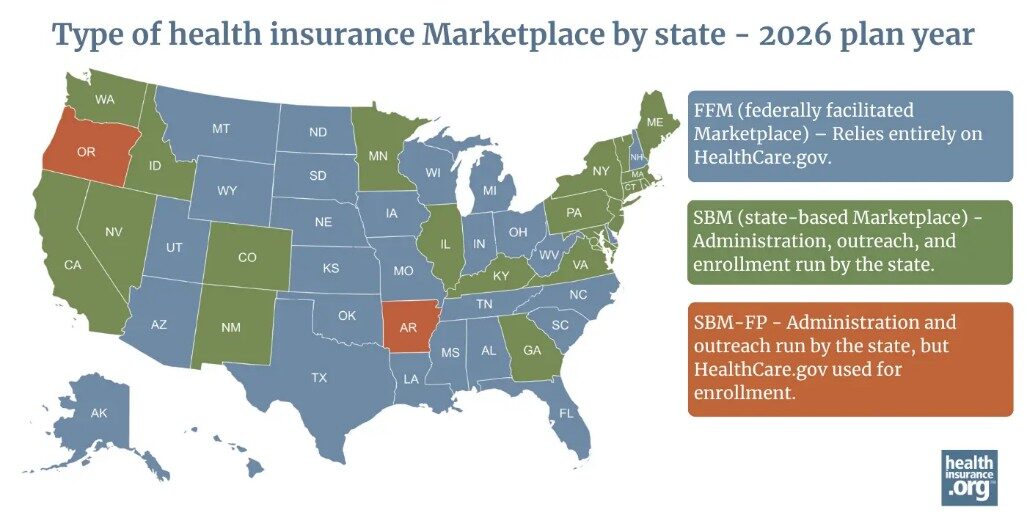

Figure 1

Introduction

At this writing, there are 20 SBEs in Plan Year 2025. The primary factors driving states to SBEs are cost savings, reinvesting marketplace user fees to meet state-specific needs, improving customer experience, and realizing greater autonomy over their insurance markets.5 States are focused on building trusted health insurance marketplace brands, improving outreach to uninsured populations through innovative advertising and engagement, extending enrollment opportunities, improving access to data to inform decision-making, and reducing coverage gaps as people move between Medicaid and marketplace plans.6 States including California, Colorado, Georgia, Kentucky, Massachusetts, New Jersey, New Mexico, Pennsylvania, Virginia, and Washington demonstrate how SBEs can create more flexibility, improve enrollment, and give states greater control over their residents’ health coverage.

Analysis

Since 2015, six states have transitioned to SBEs, reflecting states’ more active roles in managing health coverage.7 States can pursue SBEs to gain greater control over policy, funding, and operations, allowing for a more localized approach to affordability and access.5 One of the advantages of SBEs is that they offer states the ability to retain and reinvest issuer fees, directing these funds toward local priorities such as reinsurance, subsidies, and specialized outreach.8 The Medicaid unwinding process has emphasized the importance of coordination between Medicaid and state marketplaces to reduce coverage gaps.9 In addition, SBE states can potentially better connect with uninsured households through segmented branding, outreach, and enrollment strategies.4 In sum, SBEs may enable states to more effectively customize marketplace policy and standards, reduce costs through retained and reinvested savings, improve and localize branding and engagement, and better align and integrate with Medicaid. We explore each of these briefly below.

Through SBEs, states have more control over marketplace policy and plan management. Under the FFM model, the federal government sets uniform standards for plan certification, network adequacy, and benefit design, establishing a baseline for consumer protection and plan quality.10 With SBEs, states have the flexibility to determine standards and tailor them to local needs and priorities. For example, Massachusetts’ “Seal of Approval” allows the state to certify Qualified Health Plans (QHPs) and Qualified Dental Plans (QDPs) only if they meet the state’s defined criteria standards.11 This process ensures that plan offerings not only meet federal minimums but are reflective of Massachusetts’ specific healthcare standards.

SBEs allow states to extend or customize their Open Enrollment Periods (OEP) and Special Enrollment Periods (SEP) to meet the needs of their community. This differs from the FFM, which maintains a national OEP from November 1st to January 15th and limits SEPs to specific qualifying life events, such as marriage or adoption of a dependent.12,13 California’s SBE, Covered California, extended its OEP beyond the federal standard from November 1st to January 31st.14 States may choose to adjust their enrollment timelines to improve access, particularly during coverage transitions. Broadening enrollment windows can increase access to coverage, especially for households experiencing changes in income, transitioning from Medicaid to the marketplace, or those who may have missed federal enrollment deadlines.15

Through the FFM, the federal government sets standardized plan options through the HHS Notice of Benefits and Payment Parameters (NBPP) each year.16 These plans feature uniform cost-sharing structures like fixed deductibles and copayments. Through SBEs, states can take these plans one step further by creating state-specific standardized plan designs that reflect local needs and may simplify consumer choice. Colorado’s “Colorado Option,” for example, establishes standardized plans with defined criteria, including premium reduction targets and rate increase caps.17 This framework enables the state to hold carriers accountable for meeting affordability goals while tailoring plan features to better align with the needs of their population.

Cost reduction is another important factor in states’ consideration of SBEs, along with the opportunity to reinvest these cost savings locally. States participating in the FFM pay a 1.5% user fee on premiums for plan year 2025.18 This user fee supports HealthCare.gov operations. States can avoid these federal fees, establish lower state assessments, and retain funds that would otherwise flow to the federal exchange by operating their own SBEs. Pennsylvania’s exchange, Pennie, as an example, reinvested around $50 million in projected annual savings from their SBE for in-state needs.19 States can apply for a Section 1332 State Innovation Waiver, which allows them to implement alternative strategies for providing affordable health coverage, if they maintain the same level of coverage and affordability as the federal government.20 Many states use these waivers to create reinsurance programs, which help offset high-cost claims and lower premiums across the marketplace. For example, Georgia applies funds from its Section 1332 waiver to stabilize premiums through its state reinsurance program and its SBE, Georgia Access, which allows the state to further reinvest marketplace resources and expand outreach.21 Similarly, New Mexico’s Health Care Affordability Fund, created through Senate Bill 317, uses state revenue to reduce premiums and out-of-pocket costs for residents purchasing coverage on ‘beWellnm.’22 These examples show how SBEs can strengthen affordability and sustainability by enabling states to manage and reinvest the marketplace funds to serve their populations.

SBEs can provide states with the opportunity to build a trusted, state-specific marketplace brand and create outreach campaigns tailored to local populations rather than relying on the federal model. With greater control over messaging and marketing, states can improve communication, reduce consumer confusion, and connect more closely with uninsured and underserved communities. New Jersey’s Get Covered SBE experienced significant enrollment growth after its launch. In 2025, New Jersey reported that enrollment had more than doubled since the state took over the marketplace, thanks to targeted outreach and state-funded subsidies.23 Another example is Kentucky’s SBE, ‘kynect,’ which emphasizes meeting community needs through local outreach and engagement. The state partners with county agents and ‘kynectors,’ or trusted local professionals, to help residents navigate enrollment and access benefits, especially in rural areas with limited internet or digital literacy.24 By tailoring outreach and branding to reflect state needs, SBEs demonstrate how localized marketplaces can build strong community trust and enrollment.

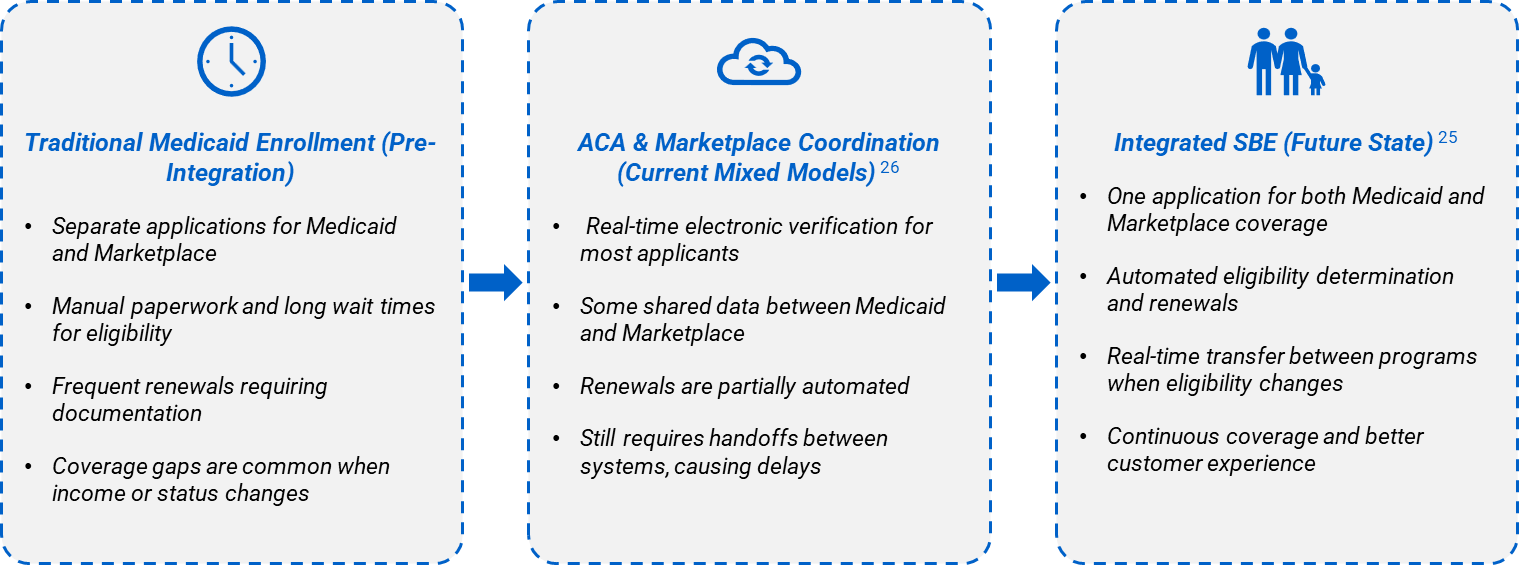

Align Marketplace and Medicaid

SBEs help states coordinate marketplace coverage with Medicaid to reduce coverage gaps and make it easier for people to stay insured when their eligibility changes. In Virginia, the Health Benefit Exchange determines whether applicants qualify for Medicaid and automatically transfers that information to the state’s Medicaid agency, creating a faster and smoother process for residents.25 Washington’s Healthplanfinder uses a single application that connects both Medicaid (which Washington names as Apple Health) and marketplace plans, allowing applicants to apply once and receive real-time eligibility results for either program.26 These integrated systems simplify the customer experience, reduce administrative barriers, and help ensure residents maintain continuous coverage.

Figure 2

What MGT Thinks

- Does the current marketplace model deliver the best value for your state and its residents?

- Are your residents able to maintain continuous coverage when their eligibility changes?

- Is your current marketplace effectively addressing affordability challenges?

- Does your state have access to the data needed to improve enrollment outcomes?

- Is your marketplace building trust with residents and reaching the people who still lack coverage?

Call to Action

MGT has proven experience supporting states with marketplace strategy and implementation, including recent extensive work with Georgia Access Health Exchange. Through research, stakeholder engagement, and project management, MGT has helped states successfully plan, launch, and scale their SBEs to meet their goals.

- Marketplace Readiness Assessment: Evaluate alignment of current model with state goals.

- Affordability Strategy Design: Model reinsurance, fee reinvestment, and subsidy strategies.

- Policy and Market Design Support: Explore state-specific enrollment policies and plan design flexibilities.

- SBE Transition Roadmap: Define governance, timelines, and implementation steps.

- Implementation Planning & Project Management Office (PMO): Provide execution support for SBE planning and launch.

Are you assessing whether your current marketplace model meets the needs of your community? Schedule a discovery session to explore how an SBE could help your state achieve its specific goals.

References

1 https://www.cms.gov/CCIIO/Resources/Fact-Sheets-and-FAQs/state-marketplaces

4 https://unitedstatesofcare.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/03/Benefits-of-SBMs.pdf

8 https://shvs.org/current-considerations-for-state-reinsurance-programs/

10 https://www.cms.gov/newsroom/fact-sheets/hhs-notice-benefit-and-payment-parameters-2025-final-rule

12 https://www.healthcare.gov/glossary/open-enrollment-period/

13 https://www.healthcare.gov/glossary/special-enrollment-period/

14 https://www.coveredca.com/support/before-you-buy/enrollment-dates-and-deadlines/

17 https://leg.colorado.gov/bills/hb21-1232

18 https://www.cms.gov/newsroom/fact-sheets/hhs-notice-benefit-and-payment-parameters-2025-final-rule

20 https://www.cms.gov/marketplace/states/section-1332-state-innovation-waivers

21 https://georgiaaccess.gov/what-is-georgia-access/

23 https://www.nj.gov/dobi/pressreleases/pr250220.html

24 https://khbe.ky.gov/Agents-kynectors/Pages/Agent-kynector-Portal.aspx

25 https://www.marketplace.virginia.gov/sites/default/files/2023-08/2023.08.04-Assister-FAQ.pdf